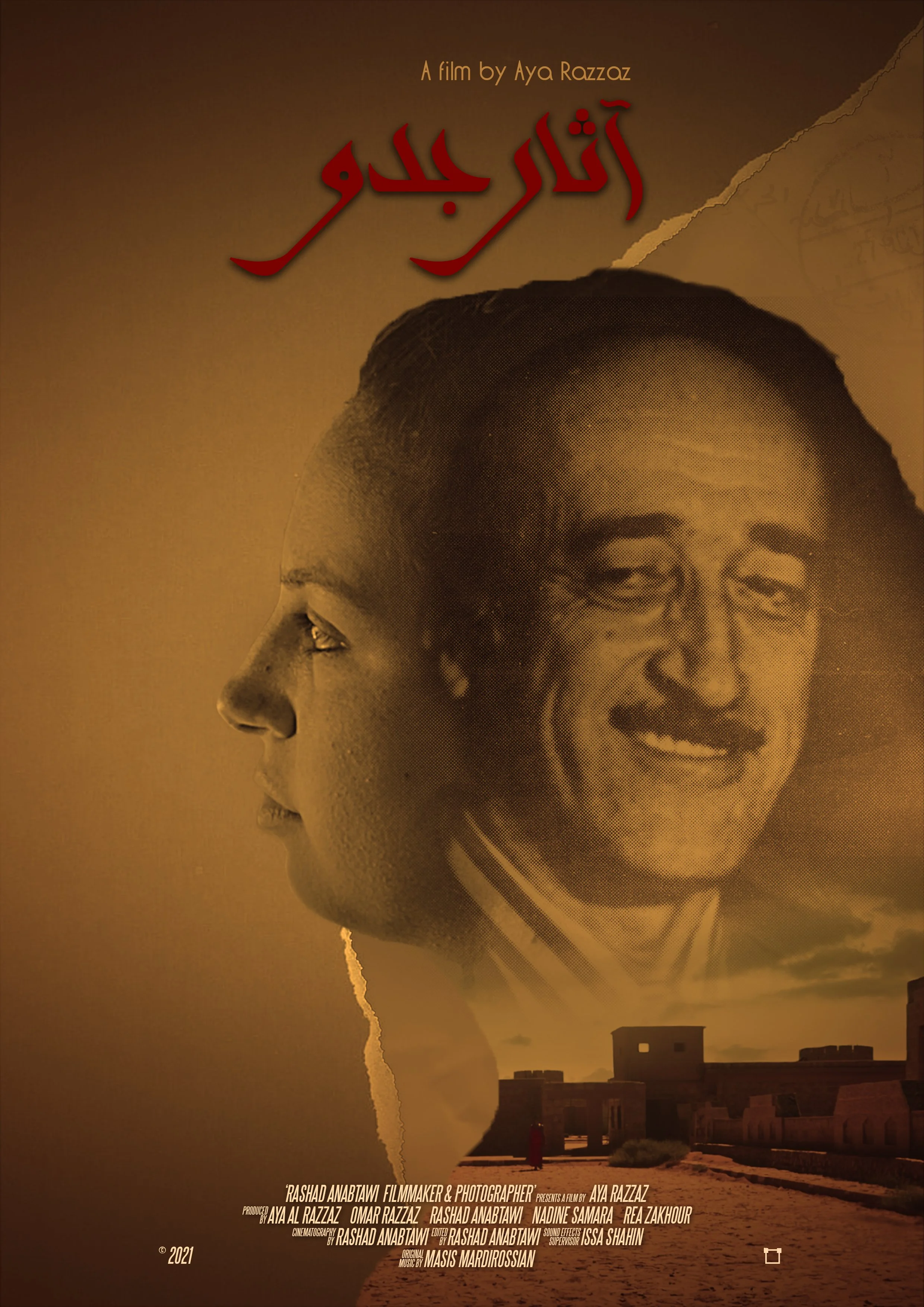

RELEASE DATE: 2022

DIRECTED BY: Aya Razzaz

PRODUCED BY: Aya Razzaz, Omar Razzaz, Rashad Anabtawi, and Nadine Samara

A memory explores an abandoned prison to uncover family secrets and bring light to human rights violations through mysterious long lost letters. "Athar Jiddo", translated to 'my grandfather's antiquities', is a short experimental film.

It's experimental in the sense that it does not follow a linear narrative structure, bouncing back and fourth between the symbolic past and metaphoric future.

The film is the brain child of Aya Razzaz, a Pennsylvania dance instructor, who has a deep heritage ingrained in The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. The story revolves around an imprisoned man, jailed in a prison in the desert, who writes letters to his family as a way to cope.

The interpretive dance was choreographed by Aya Razzaz. The letters are real, written by her grandfather in the 1950's. These letters recently resurfaced and sparked Aya's curiosity as she began investigating, with her father, the near forgotten history of Al-Jafr prison.

LANGUAGE(S): Arabic with English subtitles

EDITED BY: Rashad Anabtawi

SOUND DESIGN BY: Issa Shahin

MUSIC COMPOSED BY: Masis Mardirossian

ABOUT ATHAR JIDDO

Al Jafr- Prison

“A warning of what hell is like”

Al-Jafr Prison is located in the south of Jordan, only a few kilometers before the governorate of Ma’an. Off into the desert, it once held many political prisoners.

Joby Warrick, a pullitzer prize winning journalist wrote in the TIMES article, “The most notorious of Jordan’s prisons is the old fortress of al-Jafr, known for decades as the place where troublesome men went to be forgotten.”

It was the site of many human rights violations in the early to mid 19th century. According to the TIMES article,

“Newly arriving prisoners were routinely beaten until they lost consciousness. Others were flogged with electric cables, burned with lit cigarettes, or hung upside down by means of a stick placed under the knees, a position the guards gleefully called ‘grilled chicken.’”

In 1979 the Jordanian Government decided to scrub its stained history clean by trying to renovate the site into a training and vocational center, that lasted about 4-8 years, but then failed due to the far out site. The branding of the vocational center still remains, but the site officially belongs to a military faction titled “Guwat Al-Musalahein”.

The article continues:

“ ‘There’s a terrible loneliness,’ wrote filmmaker David Lean, who shot parts of Lawrence of Arabia on the same mudflats in 1962 and pronounced the place ‘more deserted than any desert I’ve ever seen.’ His picture editor, Howard Kent, would describe al-Jafr as, simply, ‘a warning of what hell is like.’

Typically a film crew would spend hours if not days on location before filming starts. Scouting spots for particular shots, noting where to add lighting, making sure the space is safe for the cast. Our pre-production research was very different. The prison doesn’t even appear on maps of Jordan due to its controversial history of inmate brutality. The film crew was only given access to the prison for one day, so this birds eye view of Al-Jafr prison was all production had, along with letters Munif Razzaz had written about the prison while he was there. Director Aya Razzaz (Munifs granddaughter) had spent the past year reading obsessively about the different spaces within the prison, how these political prisoners would spend their time there and how Aya Razzaz could move in these spaces.

History on Munif’s years after being released from Al-Jafr Prison.

Munif Razzaz (1919-1984) was a Jordanian physician, political thinker/writer, and one of the founding fathers of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party. In 1957, he was imprisoned in the Al Jafr Prison, established exclusively for political prisoners, along with dozens of political opposition activists from various progressive parties. During his four years in this desert prison, a dialogue was exchanged between Munif and his wife, Lama, in the form of letters.

Sixty-six years later, their granddaughter, Aya Razzaz, finds and reads these letters and returns to the same prison, now closed and abandoned. Armed only with these written memories, she excavates and retraces her Jiddo’s (grandfather in Arabic) footsteps within the confines of those same walls, coming face to face with a grandfather she never met and memories she never knew she had.

PRE-PRODUCTION

Pre-production was done all remotely as Aya Razzaz was not in Jordan when this Idea came to be.

In order to get this done legally, the production needed to make sure that the permits were all ready and signed before going to the location of Al-Jafr. It was a 3 hour drive, it would have been a nightmare to be sent back because of a lack of paperwork.

Unfortunately we didn't have a chance to scout before going to Al-Jar, so we didn't know if we had electricity or a place to keep gear, or if the indoors were accessible, and so on.

The challenging part of the pre-production process was finding the prison as it has changed in purpose multiple times. It is now a closed national vocational training center remodeled over the prison. The original architecture is still there, while in other places it is completely new.

Due to its controversial history, many people don't know that this was a prison while others refuse to acknowledge that this is a prison. So getting permits had multiple barriers when it came to language and logistics

PRODUCTION

It took us about 3 hours to make it to Al-Jafr. Upon arriving we drove deep through the city and finally found the location. Aya Razzaz phoned her father and they shared an emotional moment together as they walked through the hallowed halls of where their ancestors walked.

The production process took us by surprise as the real history of Al-Jafr Prison came to be. As Aya Razzaz and I were location scouting and planning out the shoot, excitement surged through our veins.

It was time to shoot what we had planned months prior. the moment the tripod wasn't down to begin filming a 4X4 car swerved up to the sidewalk and a man came out yelling. After hours of negation and traveling back and forth to the Al-Jafr police station and dealing with the chief of police, finally I secured 2 car escorts from the police so we could finally begin our shooting.

We were now 3 hours late to our production.

The shoot was very run and gun but because we had planned everything out before the military arrived we knew exactly what to shoot. Now, though, we had a police presence to make sure our production was not interrupted.

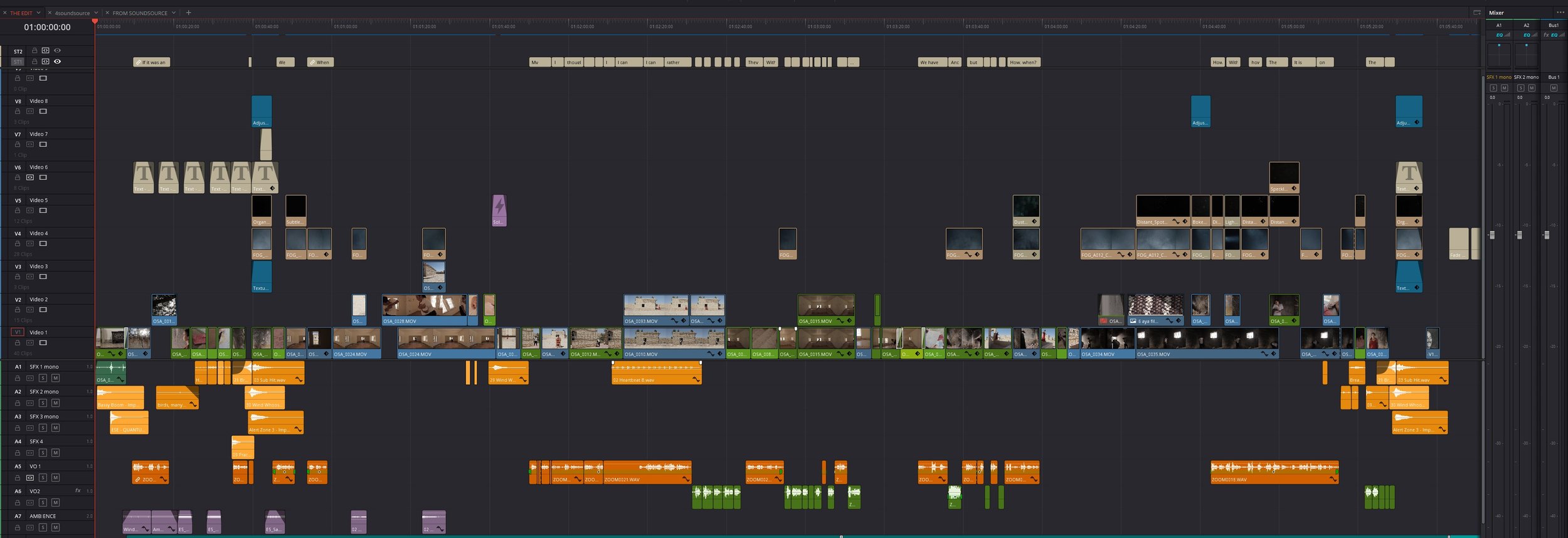

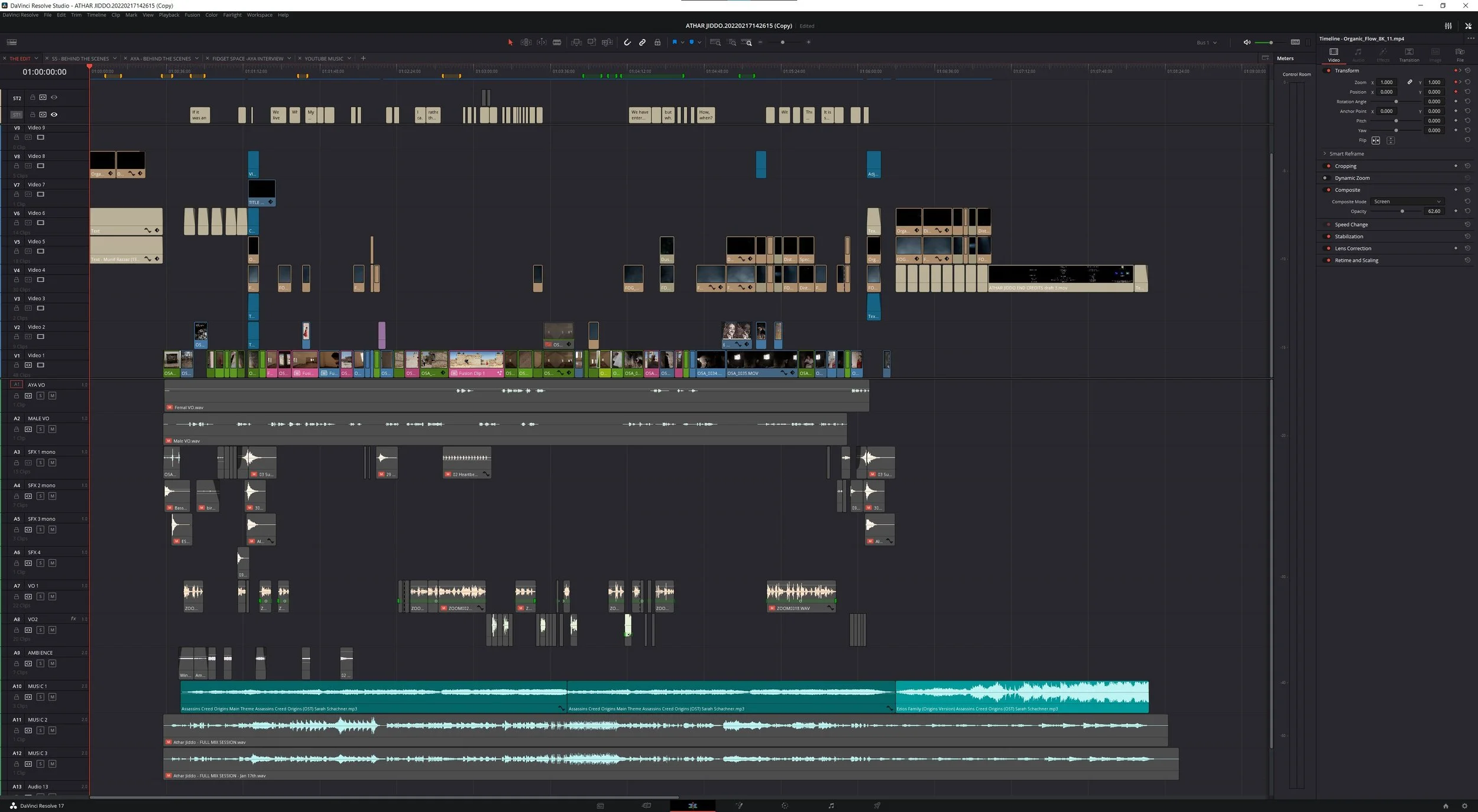

POST-PRODUCTION

Blackmagic Design Davinci Resolve Studio 17

We chose to use Blackmagic Davinci resolve 17 for the full visual post production process. We chose Davinci Resolve 17 because in early pre-production discussions, color was a really important factor into the cinematography. Though, we knew at some point minor visual effects would have to be implemented since location scouting was not available due to the restrictions on the location itself.

BEFORE & AFTER COLOR

MARKETING

THE NIGHT OF THE PRMEIRE

PRESS

The First National Jordanian Screening of Athar Jiddo